Dime Mystery Magazine

Dime Mystery Magazine is usually attributed to Harry Steeger, co-founder of Popular Publications, Inc. Steeger graduated with a B.A. from Princeton in 1925, and founded the company in 1930 after working for Dell Publishing Co. with Harry Goldsmith. Steeger's vice-president and treasurer, Goldsmith had previously been managing editor of Ace Publications. Popular was one of the major pulp publishing houses of the period that produced many, many titles, including Dime Detective, Battle Aces, The Spider, Operator #5, Terror Tales, and Western Rangers. Popular also acquired many titles from other publishing houses, such as the Frank Munsey Co. and Street & Smith, when those publishers got out of the pulp business in the 1940s. By then, the fortunes of the pulp industry were in decline.

Much of the success of Dime Mystery can be attributed to its editor, Rogers Terrill. In his early thirties when Dime Mystery debuted, Terrill had already made a career editing pulps at T.T. Scott's Fiction House where he managed titles such as Action Stories, Wings, and Fight Stories. Terrill then became Editor-in-Chief at Popular, with an editorial staff that included S.V. Farrelly, Jr. and John Bender. Each editor was responsible for multiple titles; Terrill, as lead editor, presided over thirty-one publications which had a combined circulation of 1,700,000. Editors were often given pseudonyms in all but one magazine, in order to make the staff appear larger.

Editorial departments in the magazines, which often served as advertisements for future editions, are signed simply "The Editors," and thus it is difficult to tell who was specifically in charge of editing each particular title. The ultimate responsibility for content, however, would have been Terrill's and Steeger's, as the top men in the hierarchy.

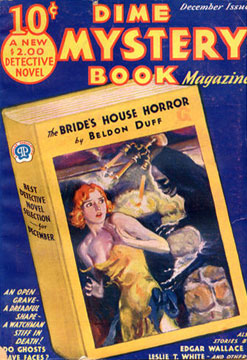

The magazine began its monthly run in December 1932 as Dime Mystery Book Magazine, which contained a "two-dollar novel" and two to three short stories for ten-cents. The content was the general mystery/ detective fiction like that found in Dime Detective. The covers of each issue featured the image of a book, on the cover of which appeared the actual cover-art. It suggested that one was indeed receiving a full-length novel for the price of a magazine. The long novel form proved problematic, however, and the title was failing after just a few issues.

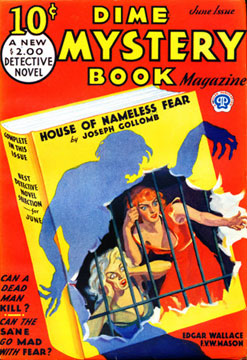

Steeger, hoping to create a companion title to Dime Detective, decided to move the magazine in a new direction with the October 1933 issue. In doing so, Steeger created a new genre: "weird menace" or "shudder" pulps. In this transformation, the magazine dropped both the "Book" from its title and the book from its cover art. Steeger also changed the form of the magazine: rather than one large novel, he included a half-novel sized novella, two to three shorter novelettes, and several short stories.

Inspired by Grand Guignol French theatre and Gothic melodrama, the weird menace genre was a combination of mystery and terror; this combination is more of a continuum, however, and occasionally, the magazine's individual stories tend towards hardboiled detective fiction on the one hand or outright horror on the other. The editors, although lax in their demand for a specific mixture of the two genres, were consistent in their demand for a natural/ rational, if often unbelievable, explanation behind the seemingly-supernatural, sensational plot twists integral to the story. Regarding the preferred content, Terrill stated:

In Dime Mystery Magazine we want the same strong emotional terror, but are more apt to demand a definite mystery angle. Here we also prefer lay characters who by force of circumstances are thrown into a terrific plight, where there is a sinister menace against the hero and heroine. We do our best to keep away from detective characters of any kind; the newspaper reporter is also overdone. Doctors, lawyers, clerks, lay figures in ordinary walk of life are the best material. And in Dime Mystery, we demand a convincing motivation for the villain's actions. He may be mentally unbalanced, may be suffering from a complex, but he should be fiendishly clever, should have a sound reason for his villainy. We will permit a strong scientific angle if within the realm of the possible, but we prefer to avoid the pseudo-scientific.... [I]n all cases the villain should be brought to heel by the direct efforts of the hero.

Villains in these stories were often physically deformed and/ or psychopathic killers who "carried out horrible and unaccountable murders" through greed- or lust-driven motives, while "the single greatest threat in the weird menace story was the dread of vivisection."

In one example, titled "Monster of His Making," a poor orphan child named Carlos is born with a bestial heart, which functions just enough to keep him alive. It cannot provide him with the force of blood flow necessary to create any emotions in the brain. This deformity and psychological state allows him to become the most steady-handed surgeon in the world, but his scalpel is also used to torture, murder, and rape women after he performs surgery on them without anesthesia:

Helen was still on the operating table, but she was stark nude, now, and her arms and legs had been securely bound to the table with stout straps. The ruddy light bathed her slender body with a crimson effulgence which emphasized rather than obscured the satin texture of her flawless skin […] His hands slid lasciviously over her nude, helpless body, bestowing unspeakable caresses. "It's a pity such beauty must be destroyed, my dear," he murmured. "Soon I shall have to open your white skin and let your bright blood flow away […] But first you shall give me something else—whether you desire it or not.... But perhaps, before it is over, you will desire it."

He has all the prerequisites for a weird menace villain: the half-supernatural, pseudoscientific explanation of madness, and quintessential sadistic torture of a beautiful female character. This quality has led one critic to suggest that the genre depended "on the idea that the image of a woman being tortured or raped was a turn-on." In "Monster of His Making," Carlos in fact forces Helen's father, Dr. Kelland, to watch her torturous surgery and sadistic rape.

Heroes of weird menace were usually "clean-cut, all-American" males, who "demonstrated that irrationality could be conquered, and that supernatural evil did not exist" by solving the mystery, saving the girl, and thwarting the evildoer's plot of destruction. In "Monster of His Making," an added twist is that Dr. Kelland uncovers the mystery in the story's beginning, and is in fact responsible for Carlos's entry into the surgical field:

"It's incredible—unheard of!" he murmured. "What sort of creature are you, my lad? What manner of being will you become when you grow into manhood—you who have no heart?"

In the end, Dr. Kelland overcomes Carlos by tipping a bottle of acid into the monster's face, rendering him blind. He forces his way out of his own bonds, beats Carlos to a pulp, and then rescues his daughter. Carlos's arrest quickly follows, or so the story implies.

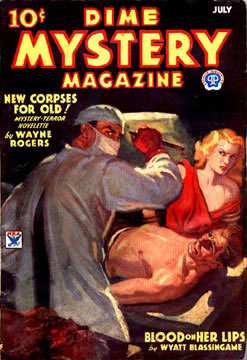

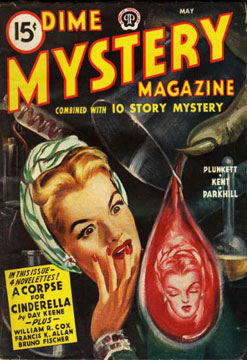

According to Steeger, Dime Mystery's publisher: "I devoted more time and attention to covers than to anything else because I figured they were our salesmen." Steeger recreated a miniature newsstand in his office, in order to determine if the cover art was attractive enough to intrigue potential buyers. Steeger is also responsible for suggesting gendered colors for his magazines. Titles aimed at men, such as Dime Mystery, used blacks, reds, and yellows. Those marketed to women featured blues and greens predominantly. Weird menace covers were notoriously sensational, and routinely depicted ghoulish villains sadistically torturing scantily-clad maidens.

Dime Mystery only credited its artists in the first two years of its history, and so many of those artists now remain unknown. Delos Palmer and Walter M. Baumhofer are two very famous exceptions, however, from the beginning of the magazine's run. Baumhofer illustrated the premier covers for The Spider and Doc Savage. He also sold work to the slicks, including Cosmopolitan and McCall's. Known interior-artists include John Fleming Gould, a Popular Publications workhorse, and Amos Sewell, who also did work for The New York Times and The Saturday Evening Post.

The art of Dime Mystery Magazine is limited to the one page cover, inside story-art, illustrations on title pages, and the advertisements; the main content was, of course, the fiction. Many popular authors appeared in the magazine, including Hugh B. Cave, Frederick C. Davis, and Wyatt Blassingame. Cave, who also went by several pseudonyms, produced at least a thousand works of fiction and published his last novel directly before his death at age 93. Cave also published non-fiction during World War II, including studies of Caribbean languages and voodoo, which he used as background material for his stories. Davis is perhaps most famous for his creation of Moon Man, a recurring dual identity hero and likely influence on the characterization of Batman. Blassingame wrote both fiction and non-fiction books, short stories for both adults and children, anthologies, and textbooks. Another particularly noteworthy contributor to Dime Mystery was Ray Bradbury, who had five stories published in the magazine before his famous novel Fahrenheit 451.

The peak of the "weird menace" phase of Dime Mystery coincided with the most profitable year for its publishing house; Popular Publications had one hundred and thirty pulp titles that were read by thirty million people a month in 1937. Since the Audit Bureau of Circulations lists Popular’s publications as a master group, combining its titles into one statistic, determining specific circulation numbers for Dime Mystery is difficult. Nonetheless, considering that Popular continued the genre in titles such as Terror Tales and Horror Stories, other publishing houses attempted to emulate the genre, and that the magazine was relatively long lived (1932-1949), we can surmise that the title was quite popular, especially during its iconic sensual, violent incarnation.

Like any good mystery plot, the denouement of Dime Mystery’s sadism phase quickly followed its 1937 climax. By late 1938, the magazine had almost entirely phased out its over-the-top sex and violence. Hoppenstand and Browne blame "formula saturation" for the demise of the sadistic phase of weird menace, and suggest that audiences had become desensitized to the violence and sensationalism of the formulaic fiction. From 1938 to 1940, the "defective detective" characters took over the content of the magazine as the "sex-sadism" was phased out. Rather than concentrating on "weird menace," the fiction contained a deformed or diseased hero detective who "protected society against the most ghastly of villains…and guarded 'normal' folk from being afflicted with the most abominable of physical terrors." Heroes were more "humanized" through their afflictions. No longer idealized, they instead overcame terrible physical obstacles and ailments. Two recurring defective detectives in Dime Mystery were Nat Perry, a hemophiliac who could bleed to death from even a minor cut, and Ben Bryn, who, because of a childhood disease, had to push himself around on a wheeled platform, which resulted in his having very muscular arms.

In 1940, the magazine reused earlier pulp covers on nine of its issues, and in March 1941, it began publishing only every other month, signaling a decline in profitability and popularity. This coincides with the demise of Popular's other weird menace/ horror titles Terror Tales and Horror Stories. Dime Mystery was only able to continue publication, however, by devolving into a more strictly detective/ mystery formula. The stories continued to feature the stereotypical rational revelation of supernatural occurrences in the summation of their plots, but only the occasional truly weird villain occurred after 1941. The heroes became "prosaic, often with nothing more than an unusual name or blighted background," in contrast to the "All-American" or the "defective detective."

During World War II, pulps had to contend with paper and metal shortages and the shifting priorities of consumers: Steeger claims that the effect of the war on pulps was "unbelievable." By November 1944, each Dime Mystery issue included the subtitle: "Combined with 10 Story Mystery," a title which, according to FictionMags Index, had only one issue. At this time, the price of Popular's "Dime" magazines rose to fifteen cents, contradicting their titles, and signaling the beginning of the end.

Struggling to make a profit, Dime Mystery upped its price to twenty cents in December 1948 before eventually folding in December 1949, sixteen years after its inception. Dime Mystery rode out the final years of the pulps better than many other magazines, but finally succumbed to the demise of the entire medium caused by post-war shifts in technology, culture, and new forms of popular entertainment.

Emily Sisler, The University of West Florida

Works Cited and Consulted

The A.B.C. Popular Publications Master Group: Publisher’s Statement of Circulations. Period ending June 30 1938.

Bernstein, Adam. "Hugh B. Cave" (Obituary). Los Angeles Times (5 July 2004): Home Edition, A2.

DeForest, Tim. Storytelling in the Pulps, Comics, and Radio. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Co., 2004.

"Dime Mystery Magazine." Galactic Central. Phil Stephensen-Payne. Sept 2012.

Eller, Jonathan R. and William F. Touponce. Ray Bradybury: The Life of Fiction. Kent: Kent State University Press, 2004.

Ellis, Doug, et al. The Adventure House Guide to the Pulps. Silverspring: Adventure House, 2000.

FictionMags Index. Contento, William G. Mailing List, last update 30 Sept. 2012.

"Guide to the Wyatt Rainey Blassingame Papers, 1955-1968," University of South Florida Libraries: Special and Digital Collections. Nov. 2009.

Grennell, Dean A. Captain Satan (1979). Windy City Pulp Stories #11, Ed. Tom Roberts. Normal: Black Dog Publications, 2011.

Haining, Peter. The Classical Era of American Pulp Magazines. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2001.

Hardin, Nils. "An Interview with Henry Steeger" (1977). Windy City Pulp Stories #11, Ed. Tom Roberts. Normal: Black Dog Publications, 2011.

Hoppenstand, Gary and Ray B. Brown. "Introduction" to The Defective Detective in the Pulps. Bowling Green, OH: BGSU Popular Press, 1983.

Hulse, Ed, ed. Blood 'n' Thunder No. 29. Murania Press, 2011.

Jones, Robert Kenneth. The Shudder Pulps: A History of the Weird Menace Magazines of the 1930's. West Linn: Collector's Editions, 1975.

Locke, John. Pulp Fictioneers. Off-Trail Publications, 2004.

Pohl, Frederick. The Way the Future Blogs: "Popular Publications, Parts 1-7." 15 Oct 2012.

Saunders, Dave. Field Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists. Oct 2012.

Sperry, Henry. "Monster of His Making," Dime Mystery Magazine, Vol. 17, No. 1. New York: Popular Publications, 1938.